Plastic Umbilical Cords and Ghosts on Factory Floors (The Story of DuPont and Our Poisoned World)

“Better Things for Better Living … Through Chemistry”

ALL THIS HAPPENED, MORE OR LESS is independent political and history journalism for anyone interested in information about how reality got here without sponsors.

»Consider buying me breakfast or coffee on Ko-Fi/PayPal, or leaving me a small tip on Venmo.

« Contact me at juno.stump@gmail.com if you need someone with experience in mock reviews, copy editing/writing, PR work, etc »

Words and research: Juno Rylee Schultz (she/her)

Research: Kylie Tuinier (she/her)

Edits by: Bex Stump (she/her) and Nathan Miller (he/him)

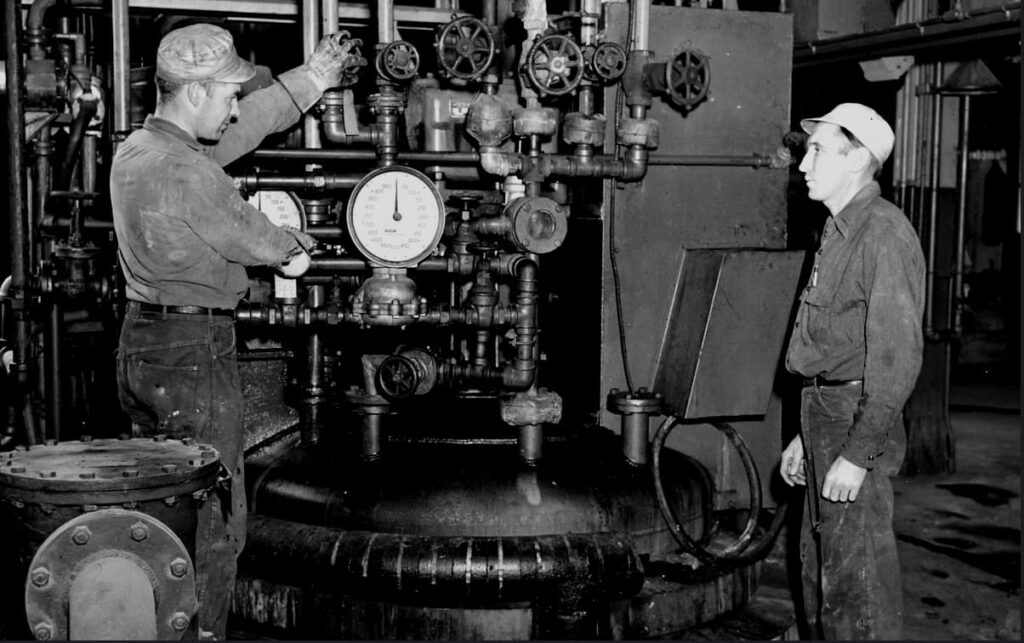

“Three coming at me at once,” a man screamed intensely, as he sprinted across the factory floors. It was clear there was nothing chasing the man, but before anyone could try to help him, or ask any questions, he jumped through a second floor window.

More employees went home sick, several of them becoming violent, screaming and inconsolable in the morning.

It was October 1924, and five of the thirty-nine employees at the Deepwater, New Jersey General Motors manufacturing plant were dead. As thirty-five employees were becoming hospitalized, the preventable tragedies were becoming national news headlines; one Nebraska headline read “Many Near Death as Result of Inhaling ‘Loony Gas’ Fumes.’

It took time for the news and dangers to spread because the regional and local newspapers were owned by DuPont, the corporation responsible, as well as the true owners of General Motors.

As the news began to spread, New York City, Philadelphia, as well as parts of New Jersey, all began to ban leaded gasoline, which had been dispersed to “about twenty thousand stations around the country.”

Scientists began calling for a nationwide ban on leaded gasoline, with one physiologist from Yale reportedly telling a gathering of engineers, “This is probably the greatest single question in the field of public health. It is the question whether scientific experts are to be consulted, and the action of the government guided by their advice, or whether, on the contrary, commercial interests are to be allowed to subordinate every other consideration to that of profit.”

Earlier that summer, DuPont had started manufacturing its tetraethyl blend of gasoline at the Deepwater, New Jersey General Motors location, and eight people almost immediately died, with “some of them in straitjackets.”

In a 1922 letter to his brother, Pierre Dupont described the tetraethyl chemical as “very poisonous if absorbed through the skin, resulting in lead poisoning almost immediately.”

In late 1924, executives from DuPont and General Motors met with the United States Surgeon General in a private meeting. It was in this meeting where DuPont and GM’s hired scientists helped “frame the debate on leaded gasoline.”

Robert Kehoe, a toxicologist and professor from the University of Cincinnati, was particularly convincing to the United States Surgeon General, though I would argue, in ways that do feel diametrically opposed to the goals and duties of both, a toxicologist, and a country’s surgeon general.

Robert Kehoe believed, firmly, with conviction, that technological progress would always lead civilization forward, and that bumps along the way were just “the prices which must be paid for the privilege (and the necessity) of living in a technological era.”

The meeting with the U.S. Surgeon General was over, once Kehoe convinced everyone in the room that low levels of lead happen naturally in the human body. He pressed that the danger that led to the deaths of the factory workers was simply from too much of the substance, at once, and proper ventilation would correct the safety concerns.

Kehoe essentially was able to do this through a mixture of charisma and junk science he had created; a study conducted by Kehoe measured the lead levels in mechanics, gas pump attendants, and tanker-truck drivers, compared their health, and concluded the general public is safe.

It was the assertion that we all have a little lead in our body, and that fans in factories, and outdoor air at gas pumps, would prevent any possible issues, because the lead couldn’t build up this way.

The Surgeon General conducted a brief investigation and couldn’t find any reason to ban leaded gasoline. The committee put together by the Surgeon General recommended publicly funded studies to measure possible long-term damage, but Kehoe and company executives argued taxpayers shouldn’t need to bear the burden of paying for it.

And so from the hallucinated ghosts and deaths of General Motors factory workers, and a sign-off from the United States Surgeon General, that leaded gasoline continues being sold to poison people–and the world–and the companies profiting off the damage and deaths are expected to study effects of their products and profits.

The results of this meeting would irrevocably influence the relationship between corporations, science, regulation and how much people are allowed to know about our collective and shared, poisoned world.

French nobleman Pierre Samuel du Pont de Nemours had befriended Thomas Jefferson in 1787, where the two had bonded over philosophy, calling Jefferson “one of the great men of the age”, so he was his first point of contact when he and his family sought exile in the United States after the French Revolution.

du Pont de Nemours had been among the primary defenders who had physically attempted to protect Marie Antoinette and King Louis XVI from a group of protesters seeking violent retribution, and so fleeing by ship to America was necessary.

In 1803, Pierre du Pont de Nemours would aid Jefferson in landing the Louisiana Purchase, as part of a strategy to avoid possible conflict with France, and as a means for America to take more land. It was during this same time that Pierre’s son built a gunpowder mill next to Delaware’s Brandywine River. Thomas Jefferson was quick to order his Secretary of War to use E.I. DuPont de Nemours & Company for America’s gunpowder and military needs, after Pierre’s son, Victor Marie du Pont, wrote a letter to request Jefferson look on his business favorably.

By the late 1800s, DuPont was making $3 million per year in military contracts, over $100 million in 2025 dollars, and it was all from exclusive contracts manufacturing smokeless gunpowder for the United States government. It is worth noting that the material was invented and patented by the US Navy, not from DuPont.

Pierre DuPont would escalate the course of profits and growth for Dupont in 1902. After he and two other family members bought out the rest of the family, Pierre and the DuPont company began purchasing every single competitor company possible. In the process, DuPont restructured everything in the company into being entirely driven by ‘Return on Investment.’

DuPont started to face some scrutiny from President Theodore Roosevelt, through the power of the Sherman Antitrust Act, but even with a 1912 verdict ruling DuPont had broken antitrust laws, the company was permitted to keep the most profitable parts of the company–the smokeless gunpowder pieces–in the interests of national security. This came as a result of military officials testifying on behalf of DuPont’s size and knowledge being important to the country.

In the end, the court ruled that if the smokeless gunpowder portions of DuPont were removed from the company, it could lead to “injury to the public interests of a grave character.”

From the beginning, DuPont was successful from money and favorability the company received from the government.

Two years later, in 1914, World War 1 erupted across Europe, as did the profits of DuPont, and the defensive and spending capabilities of the United States military. It was also at this time that America began to experience a chemical shortage on materials necessary for constructing gunpowder, largely in part because of much of these coming from Germany, and so DuPont began working to reverse-engineer chemicals.

It didn’t take long for there to be tens of thousands of pounds of chemicals to start pouring out from the special team of chemists DuPont had assembled for the project. The deputy director urged management and leadership to build a facility dedicated to this task, saying it would be profitable and “pave the way for a vibrant system of new industries.”

DuPont soon opened up a laboratory in Deepwater, New Jersey, and began purchasing U.S. companies dedicated to producing synthetic materials that the company felt had facilities and knowledge that would prove useful.

After the war, the U.S. government would sell nearly 5,000 patents on chemicals and chemical processes, obtained from Germany during the wake and ending of WW1, to a non-profit owned by DuPont, called the Chemical Foundation Institute. The patents were reportedly valued at “tens of millions of dollars” but were sold for $250,000.

Admittedly, many of these patent processes were useless to DuPont initially, largely in part due to the German scientists and chemists intentionally putting in errors to keep their discoveries as secrets. That being said, progress would be achieved on making sense of the encoded documents from DuPont recruiting and hiring German scientists. The United States government provided some assistance in this task as well, when DuPont was struggling to track down the remaining two German chemists from WWI.

After the war was finished, DuPont was able to finance a hostile takeover of General Motors, through $50 million in funding from Pierre. DuPont wanted to become the exclusive supplier of synthetic materials for General Motors, and as the largest shareholders, and the new president, Pierre and DuPont were free to carry out the company’s goals.

General Motors was immediately restructured to perform exactly as DuPont:: entirely on Return on Investment, with no regard for longevity, or the future, outside of making the most money. General Motors previously had some research labs that were dedicated to research that was entirely that: research. It wasn’t as scrutinized or measured in terms of profitability, but rather as research labs that could lead to future patents and ideas, for General Motors, and the world. Under the new General Motors however, with Pierre DuPont as President, and his brother as DuPont’s president, it was all about researching profit-making endeavors–and nothing else.

This brings Thomas Midgley’s contributions into focus in the story of DuPont, as well as the phantoms that would soon begin haunting the hallways of General Motors.

Midgley was a chemical engineer assigned to the task of developing gasoline with better fuel efficiency. The goal was also to stop the engine knocking that was common at the time for cars. Midgley discovered two chemicals; one was ethanol, which came from excess, discarded waste from crops; the other chemical was tetraethyl lead.

Ethanol couldn’t be patented, and tetraethyl lead could–meaning DuPont and General Motors could profit on every single gallon sold. It was too much for the two profit-focused companies to resist, regardless of the knowledge that the chemical compound was poisonous to the touch.

Less than 2 years later, DuPont and other executives would be in front of the surgeon general, successfully convincing the government that DuPont would take care of testing for long-term harm, while possessing absolutely no incentive to do so.

In fact, by 1929, the University of Cincinnati are all given stacks of cash by DuPont and General Motors to fund a toxicology program, led by Robert Kehoe, which would be a major source of information for common citizens and scientists to source, even though the entire well of water was corrupted from private, non-incentivized funding.

It was around this same time that William Carothers, a researcher from Harvard, came to DuPont, as part of a research program entirely dedicated to exploring possible future chemicals, outside the bounds of what science already knew.

This program came from the idea of Charles M.A. Stine, DuPont’s chemical division head, who argued about the untapped financial possibilities DuPont had yet to uncover still. Part of the idea was that it would be easier to recruit top scientists because they could feel like they were helping humanity, instead of just trying to discover future products to sell, with it being labeled as a research program that wasn’t focused on profits.

Carothers immediately started researching polymers, and how molecules connected together, and what could be done to mimic the fibers of organic life. Carothers began exploring ways in which molecules and molecule structure could be expanded upon from standard chemical reactions.

On April 17, 1930, Carothers and his assistants had successfully created synthetic rubber, and then synthetic fibers, after removing moisture and stretching the material. By 1935, amidst a depression spell, Carothers discovered chemically, from additional research and experimentation on synthetic rubber, which could be used in clothing and cloth. DuPont was eager to celebrate the release of Nylon 66, as well as more consumer products that were helpful, everyday household items.

DuPont had hired a PR company, and was hoping to rehabilitate the public perception of the company’s image, as the general public was beginning to increasingly associate DuPont with profiting off of murder. This was largely in part from the book Merchants of Death being published in 1934, which had been informing everyone that DuPont had been a major influence on World War 1 happening, as well as the company having sold ammunition to America’s enemies, and allies, during the war.

“Better Things for Better Living … Through Chemistry” was DuPont’s new company slogan, and Charles Stine, and a woman in nylons, would unveil this new DuPont image, at the 1938 New York World’s Fair.

It was at the same time that nylons were selling out, all across the country, that Teflon was being invented by Roy Plunkett at DuPont, but the chemical giant stumbled on turning the material into useful molds–because of how resistant the material is to heat–and other useful consumer uses. This changed quickly, however, when DuPont once again had the support of the U.S. government, when the corporation would assist with–and lead–the Manhattan Project for the atomic bomb and WW2.

Thanks to a two-page letter from Albert Einstein in 1939, the United States government was made aware that Nazi scientists were working on nuclear energy, as well as nuclear weapons.

The Roosevelt administration began putting together a team of scientists and chemists immediately to deal with the building threat of nuclear war.

It became clear that the team would need a material that could withstand exposure to fluorine, hex, and other dangerous, harsh chemicals. One of the deputies from the project reached out to DuPont, stating it was of national importance, but without getting into the details of weapons and war.

A government-funded program was set-up for DuPont to research how to produce Teflon at mass scale, for the purposes of national security, though the true reasons were still kept hidden–until July 1942.

In a secret meeting, military officials, DuPont executives, as well as various gathered chemists, were all told that collaboration would get tighter, as well as more information being directly given. It was here where everyone gathered was told how the goal was to “develop a specific class of fluorocarbons whose defining feature was multiple fluorine-carbon bonds.”

Forever chemicals. Indestructible substances. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS.

Synthetic chemical compounds that aren’t naturally occurring in nature, and cannot be broken down.

Executives and everyone gathered at the meeting were told the government would pay for everything. Cost wouldn’t be an issue.

It was seen as an impossible endeavor, and not something anyone was necessarily qualified to do, but the government was primarily focused on results being delivered, and in time to respond effectively in war. DuPont was tasked with managing the program due to the company’s size and ability to routinely manage large projects.

By the end of 1942, DuPont was also tasked with manufacturing plutonium, and was being given much more information on the Manhattan Project–and its true purposes.

DuPont was especially eager to help, and it didn’t just come from financial and research motivated reasons; a few months earlier congress had become aware of the fact that GM had made a financial deal with Germany, yielding the chemistry recipe for leaded gasoline, paving the path for Hitler to have the resources to declare war on the world.

To help improve the company’s image, DuPont agreed to “limit its fee for the plutonium project to one dollar above costs.” The company also agreed to turn over the plutonium patents to the United States government. All of the Teflon patents would remain with DuPont, however, which is what the company was truly interested in, now that it had the means and intel to manufacture it at scale.

Synthetic rubber, polyethylene, and an assortment of plastic substitutes were being churned out in massive factories across several locations. Research was coming together rapidly, and compressed between executives, government officials, and scientists and chemists from all over the country.

As Charles Stine put it: “The pressures of this war are compressing into the space of months of developments that might have taken us a half-century to realize.”

Death was widespread across all the manufacturing plants; fires, chemical burns, and employees struggling to breathe were all becoming common workplace issues. Manhattan Project inspectors observed DuPont employees discussing their dread over having to work on “Devil’s Island.”

It was affecting more than the workers too.

In 1943, farmers that were downwind from DuPont’s Chambers Works were making complaints about their peach crops being destroyed. There were also cows, horses, and other farm animals experiencing health issues; this ranged from cows struggling to stand, horses being too weak to feed from fields, and plenty of dead chickens and cows as well.

There was initially concern the farmers would sue DuPont, which would make the government liable under the contract, but a secret, misinformation project was launched instead.

This program was launched inside a six-story building, accessible underground, beneath the University of Rochester, with a mission to “strengthen the Government’s interests by producing data to defend against medical legal challenges.”

The program’s first task was putting together a junk science conference on the health effects of fluorine.

The minutes are missing from the United States National Archives, so it’s unclear what was discussed at this meeting, but we do know who was in attendance; Manhattan Project officials, a DuPont executive, and researchers from the University of Rochester and the University of Cincinnati.

The intentions of DuPont, as well as the government’s involvement, were outlined more deeply in the sand after there were some deaths at DuPont’s Deepwater plant that the Manhattan Project wanted to investigate. When DuPont was asked for Teflon samples from the government, so they could investigate the causes of death more thoroughly, DuPont responded to the officials by saying the company considered what the government was purchasing as a “packaged product.”

The company stated they were not interested in investigating the materials involved. A Manhattan Project memo from a month after the incident articulated the situation more plainly, stating: “DuPont is reluctant to release samples of their own commercially produced material since several of the components thus far identified give good promise for commercial use.”

When lawyers representing the nearby farms that were affected by the Manhattan Project and DuPont’s fumes began asking for information on the chemicals used, in 1943 and 1944, DuPont executives stalled, re-directed, or simply said it was related to a secret military program.

In 1945, after the atomic bombs were dropped in Japan from America, the farmers began trying to press for information and sue again. It was at this time that the United States government blocked the release of the information, citing “military security” as the reason.

Farmers continued to hit blocks as they continued to try to sue, with the government wanting to prevent roadblocks to its continuing nuclear and military programs.

It was in 1950 when DuPont’s big breakthrough with Teflon would arrive. The company approached 3M (Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company) for advice on making Teflon easier to use for commercial products.

3M began getting involved with chemical creation in 1945, going as far as hiring former chemists from the Manhattan Project to aid in the company’s plans to commercialize synthetics. The company was eager to experiment with fluorine, and to expand on its biggest offerings, which at the time was a water-resistant sandpaper.

3M scientists and chemists aggressively pursued the limitless potential and future they all imagined, which included ads being put out in magazines that read “WANTED – JOBS FOR A TRILLION NEW CHEMICALS.”

Pesticides from wartime gases, fertilizer from material formerly used for combat explosives, and synthetic plastics found their way into grocery bags, Tupperware, Hula-Hoops, medical equipment, Saran Wrap, shower curtains … the new plastic and synthetic materials were inescapable, as were the profits of the companies involved.

This is why 3M was able to give DuPont clear and easy advice when the company asked about how to make Teflon work better for their goals, which was to mix the Teflon particles with a PFOA solution. This proved to be the necessary fix.

In the 1950s, consumer safety advocates and some politicians began to ask questions and push for regulation of chemicals and synthetic materials, but these efforts were often called “anti-America”, or interrupted in other ways, by the PR efforts of DuPont and 3M, who had hired PR firms to lobby against lawmakers, journalists, public conversations, and existing science.

In 1958, congress did finally pass a law requiring safety testing for chemicals in food, food packaging, and food cookware. The bill was hobbled greatly by the chemical industry lobbying to grandfather thousands of chemicals past the law, including PFOA and Teflon.

By 1959, DuPont began working to market Teflon products to the public, with the company reportedly inviting reporters over for a pancake demonstration, showcasing how the Teflon lined pan didn’t stick to food at all.

By 1961, DuPont’s chief toxicologist informed executives that data from new internal testing showed the PFOA chemical was damaging to the kidneys and livers of animals. Internal testing on the dangers continued within DuPont–as well as 3M–but this information was not released publicly.

Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring started to change the public perception of synthetic chemicals and materials when it was published the following year. She wasn’t revealing new information, but she was talking about it in a way that resonated with people, instead of droning on, while quoting academic papers. She discussed the toll and damage of the overabundance and over reliance on synthetic chemicals, and the havoc it was wreaking on the environment, animals, and people.

The 1970s led to a lot of public support for environmentalism, as more people began to recognize the toll that these forever chemicals were having. The Nixon administration and congress were nearly successful in passing legislation that would have given the EPA more power and resources to deal with all the synthetic chemical threats that America was beginning to acknowledge. Tragically, the chemical industry was able to successfully stop the bill from passing.

Chemical plant disasters continued to inspire support for increased regulation against chemical makers though, and by 1976 the Toxic Substances Control Act passed.

It wasn’t a complete victory.

Compromises happened when Congressman Robert C. Eckhardt–the chief architect behind this legislation–faced some lawmakers threatening to vote against the bill, if it was too strict.

Eckhardt wanted some legislation, additional protections, for a problem that was rapidly getting worse, even if it wasn’t enough, and even if it was being stripped down. It was something. It was a start.

Throughout the 1980’s, Teflon unnaturally became a natural part of daily life; the chemical would end up being in everything from lotion to electronics. Plastic and Teflon were pillars in the economic boom that took place during this time.

Company scientists at DuPont and 3M were all fully aware at this time that Teflon would take at least 1,000 years to fully break down, if it even broke down at all–but the profits were massive for both companies, and the economy, including that of the towns with manufacturing plants.

DuPont company towns found themselves supported, with its community events and financial support of schools and programs–even if the residents were unknowingly being poisoned.

Perhaps this was the tradeoff that Kehoe was speaking about, in the surgeon general’s office in the 1930s, where some people have to die for technological progress?

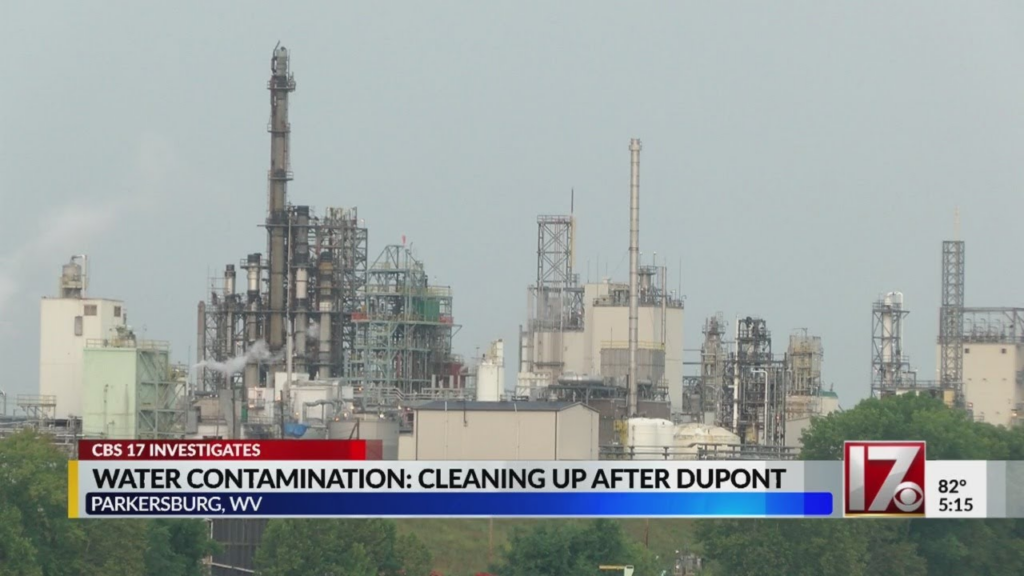

It was April 1980 when Sue Bailey was moved to the Teflon unit inside the DuPont Parkersburg, West Virginia manufacturing plant. Nine months later, Sue’s son would be born with half a nose, misshapen airways, and other birth defects.

“I was terrified he was going to die in my arms. I asked the nurse to get my pastor, then I started screaming, and they had to get me a sedative.” – Sue Baily

Sue’s baby survived, and she received a phone call the next day, from DuPont’s doctors, who wanted to inform Sue that the birth defects were routine injuries. This was as Bucky Bailey was being transported to a Children’s Hospital in Ohio to undergo a few dozen surgeries.

Sue Bailey returned to work and found a memo with a 3M study that discussed how there were birth defects in the eyeballs and eyes of unborn rats, if they were exposed to PFOA while mothers were pregnant. Sue took the memo to DuPont’s medical office and demanded answers, but she was told there was no connection.

Sue had no choice but to keep working at the plant as she needed DuPont’s insurance coverage to pay for her son’s surgeries. She wanted to leave, for a myriad of reasons, including how much colder her work environment became. She was treated like she did something wrong, like something was wrong with her, instead of anything resembling accountability.

There were already existing, internal studies, from 3M, that 3M and DuPont were both aware of, that connected exposure to PFOA and PFOS to kidney and liver damage when workers were exposed to the chemicals.

Not far from DuPont’s Parkersburg manufacturing facility was a farm where Jim Tennant and his family lived. The farm had been here since the 1950s, and life was relatively normal for the Tennant family, outside of Jim battling some unexplained illnesses, but it all got worse after 1983.

Beginning in the early 1980s, DuPont started asking Jim Tennant, and his wife Della, if the company could purchase a portion of acreage next to the DuPont Parkersburg plant. The husband and wife initially turned their nose up at the idea of having a dump next door, but in 1983, they finally decided to sell. It would help with Jim’s medical bills, and it was land they weren’t using. DuPont also promised the company would not be dumping anything toxic, and would only throw away materials like metal.

By the 1990s, Jim and Della’s daughters were constantly sick, and the creek next to the family’s farm was a foamy texture. The water was black. Then the cattle started going blind and vomiting blood. There was one cow that the couple described in a way that will forever haunt my soul.

“It was bellowing, the awfullest bellow you ever heard. And every time it would bellow, blood would gush from its mouth and its nose. It just bellowed and bellowed, and blood just kept flying, and then it would fall down and it would try to get up.”

– Della Tennant

Jim and Della didn’t own a gun, or know of any way to put their cattle out of their suffering. They were forced to bear witness to unnatural horrors–that were brought here by scientists–twist like tentacles, and take away their farm.

The family was hospitalized with breathing problems as the dead farm animals were stacking higher than they had time and dirt to bury them with, and so Jim and Della reached out to the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection–not knowing what else to do, but knowing the landfill was responsible.

Hardship continued instead of anything changing, when DuPont was simply given a flat-rate, one-time, $250,000 fine–with no further action coming against the landfill. The matter was closed and considered handled.

It took time for the Tennant family to find a lawyer willing to attempt to seek legal action against DuPont, but by 1999, environmental attorney Robert Bilott was filing motions against DuPont, in a West Virginia federal court.

The issue Bilott encountered was being able to prove and explain that the dead cattle, the health issues, and the dying farm were connected to DuPont and its legal landfill. Robert spent months combing through documents, research papers, and anything he could find that might potentially be helpful.

In August 2000, Robert Bilott found exactly what he needed, in a letter DuPont sent to the EPA about 3M products. The letter talked about a chemical called PFOA being used at the Parkersburg manufacturing plant, and that DuPont was tracking the levels of the chemical in the blood of their employees. Bilott knew this was indicative of something, and then he found a New York Times story with a 3M press release declaring a PFOS phaseout.

Bilott presented this information to DuPont, as well as his case with the Tennant farm, and requested any and all information the chemical company possessed on PFOA and PFOS.

“The shit is about to hit the fan in West Virginia. The lawyer for the farmer finally realizes the PFOA issue. He is threatening to go to the press to embarrass us to pressure us to settle for big bucks. Fuck him.”

– DuPont lawyer Bernard J. Reilly, in an August 2000 email

DuPont was panicking internally, which also included instructing employees to remember that any document they write or share internally could be read in court rooms.

Robert Bilott spent the next few months on the floor of his office, reading through all of the documents sent to him by DuPont. The company didn’t try to make it organized or easy, and the stacks of papers went back decades. As Bilott poured through DuPont’s internal history and research of Teflon, PFOA, and PFOS, it became clear that the company knew it was poisoning people and worked extravagantly to hide it all.

Bilott learned from DuPont’s documents that the Tennant’s farm was especially poisoned because it was used as a dumping ground for “PFOA-soaked sludge from the unlined pits near the community’s public wells.”

All of this sludge was dumped at the landfill purchased next to the Tennant’s farm to try to reduce the PFOA parts-per-trillion levels of Lubeck, a suburb within Parkersburg. The company tried to hide the issue further by purchasing the town’s well field–above cost–and eliminating some sources of drinking water. When this wasn’t enough, DuPont changed its internal testing standards in an attempt to further obfuscate the real issue–all the while, documenting their crimes and attempts to hide them.

Important for his case for the Tennant family farm, Robert Bilott also found documents detailing how the Dry Run Creek was being monitored by DuPont over the course of several years. This included agents being dispatched to try to reduce the foaming in the creek, but the materials used for mitigation were toxic too, which sped up the deaths of the farm animals.

As soon as Robert had enough information to build his case, and explain everything to the Tennant family, he brought them together and laid it all out. When Bilott presented his case to DuPont’s lawyers, they immediately agreed to settle the case for an undisclosed but large sum of money.

Bilott told them that this was bigger than him, the Tennant family, and Parkersburg, explaining that no amount of money could address birth defects in babies and poisoned water everywhere. Robert Bilott was letting DuPont’s lawyers know that he had full intention of pursuing DuPont’s crimes in court.

Months later, Robert sent a 972 page letter to the Environmental Protection Agency, detailing his findings, and the danger DuPont and its synthetic chemicals had presented to the entire country.

It was rather serendipitous for Robert Bilott when DuPoint sent letters to Lubeck residents, under Lubeck Public Service District letterhead, stating that there was a chemical called PFOA, or C8, in the town’s water, but that it was at safe enough levels to drink.

Concerned citizens started reaching out to the EPA, who were beginning to direct them to Robert Bilott, as the EPA officials were still processing and reading Bilott’s 972 page letter, and what it meant. A class-action lawsuit for the town started from this, with Bilott determined to hold DuPont accountable in a way that mattered: with change, instead of being allowed to pay a fine and continue the behavior.

Bilott’s letter to the EPA pushed the government agency to begin pressing DuPont for testing and information on Teflon, PFOA, and PFOS, along with assessments on how the chemicals spread inside and outside of factories.

It was around this time that DuPont privately confirmed Teflon-coating facilities were spreading PFOA too. The factories manufacturing the material were the biggest contributors of course, with DuPont learning thousands of pounds of PFOA was coming out through smokestacks.

DuPont was still working to suppress some facts and details, but the EPA forcing cooperation, even if it wasn’t full cooperation, was beginning to bring some of the true dangers and health risks associated with Teflon, PFOA, PFOS, and other synthetic chemicals into the public light and consciousness.

Barbara Walters opened a 2003 episode of 20/20 with “alarming new information” on Teflon, and how the material was in jackets, lotion, makeup, carpet, and more products than most people likely realized. Bucky Bailey was even featured in the episode, with Sue Bailey finally feeling some vindication, even if it wasn’t from the people who traumatized her and her child.

DuPont’s stock started falling more as people began to learn more about the company, leading executives to reach out to PR firms used by tobacco companies, in search of a way through the crisis. Like when The Merchant of Death was published in 1934, DuPont was more interested in shaping the perception of the company, and less interested in making sweeping changes internally.

The strategy given to DuPont was to work to shape the debate “at all levels” by taking control of the risk and responsibilities for the situation from the EPA. DuPont began hiring scientists that the EPA and other groups could hire for information, that way the people couldn’t be summoned as witnesses in court. It would also help DuPont shape the understanding and science of everything. DuPont’s goal was “constructing a study to establish not only that PFOA is safe over a range of blood levels, but that it offers real health benefits.”

Put differently: if DuPont could shape regulation and the science being referenced and followed, public perception and the company’s image would change in time.

Lobbyist Michael McCabe would be crucial during this time for DuPont as well; McCabe was previously an EPA chief, over a region that included West Virginia, the same group that ignored the Tennant family by arranging the deal with DuPont to continue dumping for the one-time $250,000 fine.

As junk science journalism pieces began being published in DuPont-funded papers that cited PFOA levels in consumer products as “negligible”, DuPont pushed the EPA to agree to a voluntary phaseout of PFOA chemicals.

McCabe informed DuPont executives that the voluntary phaseout wouldn’t be legally binding, or enforced, and the EPA would enjoy the voluntary aspect of the agreement easing public health concerns faster.

In January 2006, as part of the EPA’s PFOA Stewardship Program, DuPont and all major fluorochemical manufacturers would phase out PFOA by 2015. There was nothing binding in the deal. It was all a handshake agreement. There was also no information discussed in terms of where the waste would go in the meantime, or after 2015, or what any kind of clean-up could or would look like.

DuPont even got what the company was seeking most from the situation: a statement from the EPA telling the public that there were no studies the EPA was aware of that connected “current levels of PFOA exposure to human health effects.”

On January 30 2006, the EPA’s Science Advisory Board issued a report that stated PFOA was likely a carcinogen, which prompted Susan Stalnecker, part of DuPont’s PFOA response team, to request action to prevent any sort of PR situation for DuPont.

“Publicity around SAB report has linked the Teflon brand to cancer. Coverage has been broad in print and network media. Significant disruptions in our markets and consumers are very, very concerned. In our opinion, the only voice that can cut through the negative stories, is the voice of the EPA. We need RPA to quickly (like first thing tomorrow morning) say the following … ‘Consumer products sold under the Teflon brand are safe.”

DuPont’s lobbyists were able to arrange a phone call with DuPont CEO, Charles O. Holliday, and EPA chief Stephen Johnson. According to available deposition testimony, it is known Holliday pressed for Johnson to affirm consumers on the safety of products made with PFOA.

The EPA issued a statement the next day that read: “The use of PFOA in the manufacturing process does not mean that people using these products would be exposed. The agency does not believe that consumers need to stop using their cookware, clothing, or other stick-resistant, stain resistant products.”

In 2005, DuPont paid the EPA nearly $20 million to settle charges over suppressing data from the EPA. The company also reached a settlement in the West Virginia class action lawsuit, being fought aggressively night-and-day by Robert Bilott. It included $70 million in damages for those affected, as well as water filtration systems in parts of the town most affected. This also required testing, to prove people’s health and blood had been affected by the PFOA chemicals, which 80% of the town had participated in by the summer of 2006.

It was one of the largest pools of data collected during one study, and it was going to be crucial to prove that DuPont had affected the life and health of this town, and by extension, other human beings exposed to PFOA chemicals for prolonged periods of time.

The testing took time but researchers around the world were beginning to be able to truly measure the spread, damage, and chemical tenacity of PFOA, PFOS, and Teflon.

As the news began to spread, corporations like McDonald’s were beginning to announce that PFOA would be removed from their supply chains, and cities began conducting more thorough analysis of city water sources. This included New Jersey’s Department of Environmental Protection, which found “nearly 80 percent of public water systems to contain PFOA, PFOS, or both.”

The EPA wasn’t getting closer to meaningful, legislative intervention, and DuPont was beginning to grow anxious, as the company watched states clamour for different studies and standards, regulations that could threaten the company’s business model and the public’s view of the company.

As 2012 came to a close, Bilott and those affected from the West Virginia class action were starting to celebrate a discovery. The panel assembled by the West Virginia federal court discovered a “probable link” between PFOA and life threatening conditions for Mothers and fetuses. There was also a report discovered that showed “probable links” with kidney cancer, testicular cancer, thyroid disease, ulcerative colitis, and high cholesterol.

It took nearly a decade but Robert Bilott finally had the proof he needed to hold DuPont accountable for the poisoning of West Virginia, and to prove the company likely poisoned the world.

However in July 2015, just as some of the first trials were about to start, DuPont spun off into multiple companies, making the process all the more difficult.

There was finally conclusive proof that PFOA, PFOS, and Teflon made people sick and killed them over time, but the Chemours Company, the new company DuPont created for its chemicals, would reveal in court documents that it didn’t have enough money to pay for cleanup costs.

It was at this time that DuPont would acquire its rival, Dow, forming the new company DowDuPont, alongside the Chemours Company, with the assets between the companies split and moved around.

This same issue would happen with the forever chemicals that were finally beginning to face some scrutiny and regulation; by 2017, chemical manufacturers, including DuPont, had moved on to different synthetic chemicals, chemicals that could serve the same purposes as PFOA and PFOS, but were still technically different chemicals. Some information is still provided to the EPA, but much of it, including most of it, is hidden from the general public, as companies are simply able to claim chemicals as “confidential” and related to business purposes.

One of these chemicals is known as GenX, and according to Swedish researchers in 2017, this new synthetic chemical is even more dangerous than PFOA. This was later backed up by the EPA.

The chemical names, town names, company names, and the names of the victims continue to change, but the damage from forever chemicals continues to grow and spread, while still being a crisis not yet truly capable of being fully measured and understood. It is likely that this will continue, and be the way of things, as it is impossible to separate the power synthetic chemicals has over legislation, just as much as systems of power rely on synthetic chemicals to maintain and hold power—whether it be from weapons and bombs deployed and utilized in war, or from executives bending science, legislation, and chemical structures.

Our world is compromised until we push for regulation and information that sets all of us and our natural resources free from a future sold for maximum return on investment. Until that day, there is no way of truly knowing what goes inside of your body, without personally testing it.

Companies often currently aren’t required to disclose chemicals used in their products and processes, and even if they are, it doesn’t often happen. There are also plenty of companies–large and small–like DuPont that actively work to undermine–or ignore–regulations and laws.

In addition to educating others about the lurking dangers in our public water, we can all work to help each other stop using products we know to be contaminated with dangerous chemicals, while continuing to demand better and more conclusive regulation. Our future, and the future of everyone and our world, deserves to age naturally, to live with organic memories, without plastic and chemicals contaminating and killing us prematurely. It is not too much of an ask or demand in a world we all share.

STEPS YOU CAN TAKE TO KEEP YOURSELF AND OTHERS SAFE

- See what the companies and their suppliers say about PFAS and PFOS on their websites. Look for pledges that state these chemicals are no longer used. If you can’t find anything–or to confirm the information if you do find it–send emails, or call customer service numbers. We can put these companies on record and build paper trails until we know we are safe.

- Check PFAS CENTRAL for information about PFAS, including companies, manufacturers, and retailers with safe, PFAS-free products.

- Test your water, especially if it comes from a public water source, or a well. If your water comes from a private company, check the company’s website or call and speak to someone. Then test your water again. Be more selective about where your water comes from because all water is not the same. It should also be noted that boiling water does nothing to filter out PFAS/PFOS chemicals. In fact, boiling water can strengthen any PFAS/PFOS chemicals that may be present.

- Get rid of ALL non-stick cookware and utensils. Replace it with cast iron, glass, stainless steel, or ceramic instead.

- Do not heat up food in plastic, or grease-resistant material packaging, including microwave popcorn.

- Stop using any furniture, textiles, clothing, or bedding that is tagged as stain or water resistant.

- Share information about synthetic chemicals, especially the dangers of PFOS/PFAS, Teflon, and GenX, as often as possible with family, friends, and in contextual situations with strangers when it comes up. WE KEEP EACH OTHER SAFE.

Leave a Reply