ALL THIS HAPPENED, MORE OR LESS | “THEY WOULD MAKE FINE SERVANTS” PART 1

ALL THIS HAPPENED, MORE OR LESS is independent political and history journalism for anyone interested in information about how reality got here without sponsors.

THEY WOULD MAKE FINE SERVANTS is a multi-part miniseries about American History and Western Capitalism underneath the ALL THIS HAPPENED, MORE OR LESS column.

»Consider buying me breakfast or coffee on Ko-Fi/PayPal, orleaving me a small tip on Venmo.

« Contact me at juno.stump@gmail.com if you need someone with experience in mock reviews, copy editing/writing, PR work, etc »

Words: Juno Rylee Schultz (she/her)

Edits: Morgan Shaver (they/them), Nathan Miller (he/him), and Bex Stump (she/her)

“Around 1776, certain important people in the English colonies made a discovery that would prove enormously helpful for the next two hundred years. They found that, by creating a nation — a symbol, a legal unity called the United States — they could take over land, profits, and political power from the favorites of the British Empire. In the process, they could hold back a number of potential rebellions and create a consensus of popular support for the rule of a new, privileged leadership.

When we examine the American Revolution this way, it was a work of genius, and the Founding Fathers deserve the awe they have received over the centuries. They created the most effective system of national control devised in modern times and showed future generations of leaders the advantages of combining paternalism with command.”

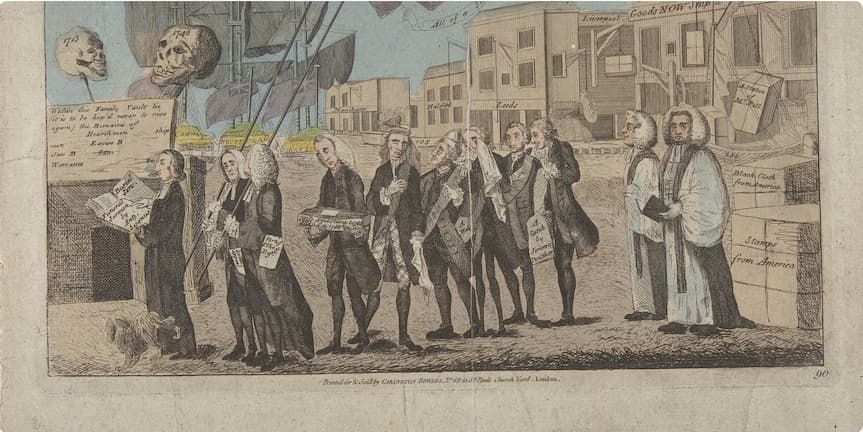

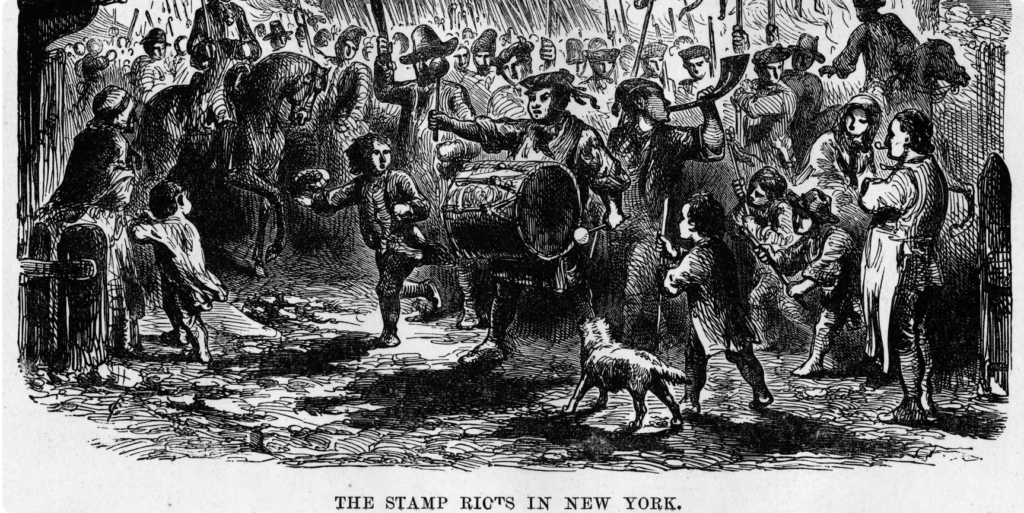

It was the 1760s, and there were organized uprisings and rebellions happening consistently across towns, villages, cities, and the countryside that would soon be called the “United States of America.”

These conflicts scarcely had anything to do with British rule at the time, but rather had everything to do with frustrations coming to a boil over growing wealth inequality and a disparity in what the law meant for everyone.

What was supposed to mark the beginning of a new world was already starting to resemble the early stirrings of Western capitalism.

It was everywhere you looked during those days.

In 1763, The Boston Gazette wrote that “a few persons in power were keeping people poor to make them humble,” while The New York Gazette received a letter from a reader who asked: “Is it equitable that 99, rather than 999, should suffer for the Extravagance or Grandeur of one, especially when it is considered that men frequently owe their Wealth to the impoverishment of their neighbors?”

It was the same situation in the countryside, where the majority of people lived. Though they were more spread out, their conditions and grievances were very much the same.

Organized protests were spreading across each of the colonies, and it was becoming increasingly difficult for the wealthy merchant class of colonists to quell the growing unrest. By 1760, there had already been nearly thirty uprisings aimed at overthrowing local colonial governments, as well as six Black slave rebellions and forty riots of “various origins.”

Control was beginning to slip from the grasp of the ruling class of colonists who saw themselves wedged between what Alexander Hamilton described as “countrymen with all the folly of the ass and all the passiveness of the sheep” and a ruling British elite they hoped to redirect everyone’s anger to.

According to A People’s History of the United States, “The philosophy of the Declaration — that government is set up by the people to secure their life, liberty, and happiness, and is to be overthrown when it no longer does that — is often traced to the ideas of John Locke in his Second Treatise on Government, published in English in 1689, when the English were rebelling against tyrannical kings and establishing parliamentary government.”

The Declaration of Independence spoke of government and political rights while expressly ignoring the existing inequalities in property. There was an active effort to strain the eyes, to see freedom and equality, without acknowledging the substantial differences in financial power, land ownership, and accumulated property. It was the insistence of a brand-new board game — a fresh and fair start for everyone — without addressing the most major issues.

The idea was to form an alliance with the growing middle class — the emerging group of artisans, independent farmers, and smaller merchants — even if just partially, socially, and at times when it was most convenient. This alliance served as a buffer between the upper class and indentured servants, slaves, and the rest of society that wasn’t included in the description of “the people.”

It also allowed the upper class to redirect the growing hostility of a society that was becoming increasingly class-conscious and beginning to recognize that “the new world” was little more than “England, Part II.”

As Howard Zinn explains in A People’s History of The United States, “Middle-class Americans might be invited to join a new elite by attacks against the corruption of the established rich.”

The plan was for the middle class to be governed by the upper class, without there being much discussion about it, while those in power — from the upper class — would “make concessions to the middle class, without damage to their own wealth or power, at the expense of slaves, Indians, and poor whites.”

As Zinn puts it:

“This bought loyalty. And to bind loyalty with something more powerful even than material advantage, the ruling group found, in the 1760s and 1770s, a wonderfully useful device. That device was the language of liberty and equality, which could unite just enough whites to fight a revolution against England, without ending either slavery or inequality.”

It was easy to understand why someone like John Locke could say he believed in liberty and freedom, while also expressing regret that the labor of poor children “is generally lost to the public till they are twelve or fourteen years old,” and how children from families receiving relief should “attend working schools” so they can be “from infancy … inured to work.”

John Locke was a wealthy man, with a fortune built on investments in the slave trade, loans, mortgages, and even the first issue of stock for the Bank of England.

So too was Thomas Paine, whose aspirations — nearly sixty years after the publication of Locke’s Second Treatise on Government — led him to publish Common Sense. Written with a very specific and neutral tone, it sought to manipulate class outage into a new, gray, moldable patriotic vehicle to win the American Revolution for everyone considered important in the new country.

It was as John Locke had said, when articulating which people he was speaking about: “I don’t mean the mob … I mean the middling people of England, the manufacturer, the yeoman, the merchant, the country gentleman …”

When the Declaration of Independence was read aloud to inspire and stir up the public in Boston’s town hall, it was delivered by Thomas Crafts, a leader from a conservative faction that had long opposed military action against the British.

Four days later, riots broke out in the streets, with voices crying, “Tyranny is tyranny let it come from whom it may!” Everyone in the colonies had learned that the rich could avoid the draft by paying for substitutes, while everyone else would be forced to serve.

This was for the people, but it would not be fought with people.

War. War never changes.

“They brought us parrots and balls of cotton and spears and many other things. They willingly traded everything they owned. They were well-built, with good bodies and handsome features. They do not bear arms, and do not know them; for I showed them a sword, they took it by the edge and cut themselves out of ignorance. They have no iron. Their spears are made of cane. They would make fine servants. With fifty men we could subjugate them all and make them do whatever we want.”

— Christopher Columbus, in his log, shortly after his sailors first came to shore in the Americas

Christopher Columbus found it remarkable how trusting the Arawak people of the Bahama Islands were, and how eager they were to share their resources. For a company of conquerors looking for gold and anything they could bring back to the King and Queen of Spain, it was the perfect greeting.

This was the first expedition that Christopher Columbus and his battalions of men would go on. There would be many more before the Arawak people were wiped out from the lands where they had once lived.

Spain was one of the latest nation-states, a grouping of people ruled by a power bent on further expansion, with the help of its peasants and the rest of society aimed at this same goal. Expansion. Growth. Reaching what its rulers believed to be the nation’s fullest potential.

Like other nation-states at the time — England, France, and Portugal — Spain was hungry for gold and power. The nobility ruled absolutely, while owning over ninety percent of the country’s land, while peasants worked the fields and attended the Catholic Church.

It was the 1490s, and Spain had recently exiled the Jews, the Moors, and anyone who didn’t fit the country’s image of what the future was to look like. Jews were given the “choice” to convert to Catholicism before being banished — but what kind of choice is that?

It was bloodier and more violent than words on paper could ever hope to honestly convey.

Everyone in power had their minds fixed on gold, silk, spices, and land — but gold above all else. Spain was no exception.

With Constantinople conquered by the Turks, the Mediterranean sea routes to Asia were closed to Spain. The alternative was to sail around the southern tip of Africa, but that expedition was already being accomplished by the Portuguese.

Columbus miscalculated the distance required to reach Asia by the route he proposed to the King and Queen of Spain. But since the Americas were in the way, his first voyage was considered a success — rather than a failure, ending with the Santa María and its two companion ships running out of provisions.

Columbus was promised a substantial incentive package by the King and Queen if his expedition proved successful: “10 percent of the profits, governorship over new-found lands, and the fame that would go with a new title: Admiral of the Ocean Sea.”

He was a merchant’s clerk up to this point, which didn’t come with any real power or money, so it’s easy to understand his decision to test his sailing skills against the possibilities of fortune.

There is nothing that can be done — or that should be done — to try to understand the horrors that came next at the direct wishes of Columbus, with some of the most horrid things intentionally obfuscated or warped in the reports he sent back to Spain.

It was October 12, 1492, about a month after Columbus and his crew of thirty-nine crew members had set first sail, and a sailor named Rodrigo spotted signs of land — moonlight glinting on white sand.

Rodrigo called out his discovery and celebrated the continued progress of the crew’s shared mission, and also because the first man to spot signs of land was to get: “a yearly pension of 10,000 maravedis for life.”

But the fame and reward went instead to Columbus, who claimed he had seen a light the evening before and thus “got the reward.”

With gold in their eyes, Columbus and his men approached the shore the following morning, and were greeted eagerly by Arawak swimmers who came out to meet them.

Columbus and his men found a peaceful people, living in village communities, surviving and thriving together through agriculture and weaving yarn.

The greetings were short-lived, however, as some of the Arawak “wore tiny gold ornaments in their ears,” which led Columbus to take many of them prisoner aboard his ship, insisting that the men from Spain be taken to the source of the gold.

Columbus and his prisoners sailed to the nearby island of Hispaniola, where they found “bits of visible gold in the rivers, and a gold mask presented to Columbus by a local Indian chief,” which filled the conquering men with even grander visions of wealth.

A military outpost was constructed — the first European base in the Western Hemisphere — for the purposes of finding and storing any and all gold from the island. Columbus left a few dozen men at the outpost before leaving to search for more gold and resources.

When some of the island’s people refused to trade, Columbus and his men resorted to violence, carrying out stabbings and killings.

As winter set in, Columbus temporarily returned to Spain with his prisoners, sharing exaggerated reports of their findings in hopes of securing further royal support and funding for future expeditions.

“The Indians are so naïve and so free with their possessions that no one else who has not witnessed them would believe it. When you ask for something they have, they never say no; to the contrary, they offer to share with anyone.Hispaniola is a miracle. Mountains and hills, plains and pastures, are fertile and beautiful. The harbors are unbelievably good. There are many wide rivers, the majority of which contain gold. There are many spices, and great mines of gold and other metals.”

— Christopher Columbus, in his log, shortly after his sailors first came to shore in the Americas

Columbus ended his report with a request for more help from the crown in exchange for “as much gold” and “as many slaves” as they wanted.

To be sure his request would be honored, Columbus reminded the King and Queen that God was on Spain’s side, saying: “Thus the eternal God, our Lord, gives victory to those who follow His way over apparent impossibilities.”

The King and Queen of Spain immediately approved the second expedition, spurred largely by Columbus’s exaggerated promises.

This time, Columbus was provided with even more ships — seventeen instead of three — and a staggering 1,200 men instead of the previous conquest mission’s thirty-nine. From then on, Columbus surged through the islands of the Caribbean, taking prisoners aboard his ship as both slaves and guides to the gold and riches Columbus and his crew were seeking.

Many of the villages would be deserted — completely empty — when Columbus and his crew arrived. It was clear people had been there, just it was clear that word of Columbus’s intentions had already spread across the islands.

Eventually, Columbus, his crew, and all their captives made their way back to Haiti, where men from the previous expedition had been left at an outpost. What they found was evidence showing that all of the men had been killed after searching the island for gold and taking women and children as slaves for sex and labor.

After taking a survey of events, Columbus ordered parties of men into the center of the island — and all around it — in search of gold fields, or anything valuable.

Nothing of real value was found after ripping the island apart, all that was accomplished was robbing the environment of its natural and previously untarnished and untouched beauty. With this, Columbus made a significant change of plans: he would fill his ships with as many slaves as possible to give to the King and Queen of Spain as a substitute for gold.

Columbus stood to benefit from 10 percent of all gold collected, so whatever money was made from unkept slaves would fill his wallet some. He would then, of course, take his cut from the human slaves as well.

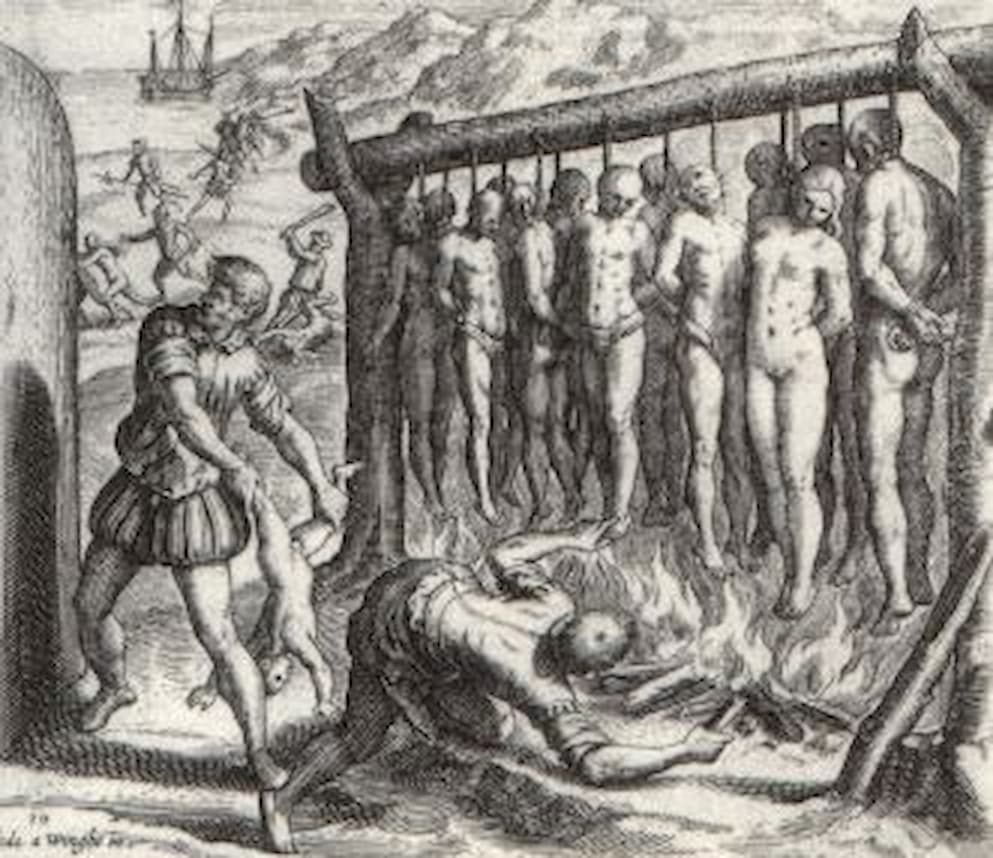

It was 1495. It was probably a beautiful day above Haiti and the Bahamas, like it is most days when people visit the islands on vacation. But if you were on the beaches that day, you would have seen over 1,500 slaves — men, women, and children — being loaded into pens, herded like animals because that’s exactly how Christopher Columbus and his men saw them. Each area that contained imprisoned slaves was guarded by armed Spaniards and trained dogs.

Out of those 1,500 captured slaves, the “five hundred best specimens” were loaded onto ships to be sold by the archdeacon. Two hundred slaves didn’t make it, though, and died on the way back to Spain. The slaves that made it were praised by the archdeacon as “naked as the day they were born” while simultaneously showing “no more embarrassment than animals.”

Columbus remarked: “Let us, in the name of the Holy Trinity, go on sending all the slaves that can be sold” through the human trafficking network he established with the church and his country.

Still, the slaves weren’t enough to fulfill the promises of overflowing pockets of gold that Columbus had promised to his masters, the King and Queen of Spain — or any of the other delusions he had invented. So, Columbus and his men turned to Cicao, a province in Haiti they were convinced was lined with gold.

When they arrived, they ordered every single captured slave who was fourteen or older to collect a certain quantity of gold every three months. If the slaves brought back the required amount of gold, they were given copper tokens to wear around their necks. Anyone found without a token was executed — hands cut off, left to bleed to death.

As Howard Zinn recounts in A People’s History of the United States:

“The Indians had been given an impossible task. The only gold around was bits of dust garnered from the streams. So they fled, and were hunted down with dogs, and were killed.”

The Arawaks did everything they could to put up a resistance, but they were a peaceful people, unprepared for anything resembling war. These were free people who shared resources, people who swam out into the ocean to greet the same men who would later enslave them. People who when they encountered swords, squeezed them and cut themselves, not knowing they were weapons.

This had nothing to do with any supposed “supremacy” of one people over another, and everything to do with cruelty preying on innocence, kindness, and generosity. The Spaniards used their swords and horses to capture Arawaks who resisted, and executed them by hanging them or burning them alive.

The Arawaks, who knew nothing of suffering outside of sickness or illness, began committing suicide by taking cassava in a lethal manner — in a poison they created and shared with each other. Arawaks also killed their infants to save them from the enslavement of the Spaniards.

They couldn’t find any other way of being free, so they chose death.

Our primary source on what Columbus did — accounts were often omitted or softened in official logs — comes from Bartolomé de las Casas. He was involved in the conquest of Cuba as a young priest, and even briefly held slaves on a plantation he owned, before he changed his heart and became a critic of all the cruelty in the current system of life he was observing.

According to Howard Zinn, Las Casas transcribed the journals of Christopher Columbus and also put together a massive history of the Indians of the islands Columbus conquered, called History of the Indies.

Las Casas describes how society was for the Indians before they were conquered and wiped out entirely.

“Marriage laws are non-existent: men and women alike choose their mates and leave them as they please, without offense, jealousy, or anger. They multiply in great abundance; pregnant women work to the last minute and give birth almost painlessly. Up the next day, they bathe in the river and are as clean and healthy as before giving birth. If they tire of their men, they give themselves abortions with herbs that force stillbirths, covering their shameful parts with leaves or cotton cloth — although, on the whole, Indian men and women look upon total nakedness with as much casualness as we look upon a man’s head or his hands.

“They live in large communal, bell-shaped buildings, housing up to 600 people at one time… made of very strong wood and roofed with palm leaves. They prize bird feathers of various colors, beads made of fishbones, and green and white stones with which they adorn their ears and lips, but they put no value on gold and other precious things. They lack all manner of commerce, neither buying nor selling, and rely exclusively on their natural environment for maintenance. They are extremely generous with their possessions…”

— In Book Two of Las Casas’s History of the Indies, Bartolomé described how the Indians of the islands were treated by the Spaniards

As Howard Zinn puts it: “It is a unique account and deserves to be quoted at length.”

“Endless testimonies prove the mild and pacific temperament of the natives. But our work was to exasperate, ravage, kill, mangle, and destroy; small wonder, then, if they tried to kill one of us now and then … The admiral was blind to those who came after him, and he was so anxious to please the King that he committed irreparable crimes against the Indians.

“Mountains stripped from top to bottom and bottom to top a thousand times; they dig, split rocks, move stones, and carry dirt on their backs and wash it in the rivers, while those who wash gold stay in the water all the time with their backs bent so constantly it breaks them; and when water invades the mines, the most arduous task of all is to dry the mines by scoping up pans full of water and throwing it up outside.

“Husbands and wives were together only once every eight or ten months and when they met they were so exhausted and depressed on both sides they ceased to procreate. As for the newly born, they died early, because their mothers, overworked and famished, had no milk to nurse them, and for this reason, while I was in Cuba, 7,000 children died in three months. Some mothers even drowned their babies from sheer desperation. In this way, husbands died in the mines, wives died at work, and children died from lack of milk. In a short time, this land which was so great, so powerful and fertile, was depopulated. My eyes have seen these acts so foreign to human nature, and now I tremble as I write.”

By 1515, it became clear there was no gold left on any of the islands. At this point, the remaining Arawaks were taken as slave labor on massive estates known as encomiendas.

The simplest way to describe these horrid creations is to say they were like giant mansions, offering countless luxuries to conquerors and royals deemed worthy, yet completely powered by slaves.

As Howard Zinn writes in A People’s History of the United States:

“In two years, through murder, mutilation, or suicide, half of the 250,000 Indians on Haiti were dead. By the year 1515, there were perhaps fifty thousand Indians left. By 1550, there were five hundred. A report from the year 1650 shows none of the original Arawaks or their descendants left…”

Las Casas stated that there were 60,000 people living on the island of Hispaniola in 1508, and that “from 1494 to 1508, over 3 million people had perished from war, slavery, and the mines.”

“Who in future generations will believe this? I myself writing it as a knowledgeable eyewitness can hardly believe it…”

— Bartolomé de las Casas writing in History of the Indies about what he witnessed

These horrors were effectively reframed as necessary for the progression of humanity’s future, which is why they have been so carefully hidden in plain sight behind phrases like “the settlers moved into the New World.” It’s this language that prioritizes some lives over others, even though those chosen to serve “human progress” and “the future” were never given a choice in what they were made to endure.

As Howard Zinn explains:

“The treatment of heroes (Columbus) and their victims (the Arawaks) — the quiet acceptance of conquest and murder in the name of progress — is only one aspect of a certain approach to history, in which the past is told from the point of view of governments, conquerors, diplomats, leaders. It is as if they, like Columbus, deserve universal acceptance, as if they — the Founding Fathers, Jackson, Lincoln, Wilson, Roosevelt, Kennedy, the leading members of Congress, the famous Justices of the Supreme Court — represent the nation as a whole. The pretense is that there really is such a thing as ‘the United States,’ subject to occasional conflicts and quarrels, but fundamentally a community of people with common interests.”

It is in this way that territory expansion, genocide, and anything else that is considered necessary for the growth of a nation are blurred and excused as necessary for a group of people that are just looking for a place to lay their heads and rest their feet.

As Henry Kissinger put it: “History is the memory of states.” And so border lines drawn are often all that are remembered by history, unless we intentionally interrogate the past and inject the missing humanity.

What was done to the Arawaks in the Bahamas by Columbus was repeated by Cortés against the Aztecs in Mexico, by Pizarro against the Incas in Peru, and by English settlers in Virginia and Massachusetts against the Powhatans and Pequots.

In this world of violence, there is something admirable and perhaps even special about choosing empathy, as outlined by Albert Camus when he said: “In such a world of conflict, a world of victims and executioners, it is the job of thinking people, not to be on the side of the executioners.”

The United States would find ways to continue the racial subjugation introduced by Christopher Columbus, with the foundations of Western capitalism having been laid in blood on the beaches of the American islands. It would also find ways to iterate on the system in a way that would simultaneously enslave more people, while hiding more of the blood and bodies behind laws that everyone is responsible for following.

Leave a Reply