Silent Hill 2, and the Reconciliation of Being Human

» Consider buying me breakfast or coffee on Ko-Fi/PayPal, or leaving me a small tip on Venmo.

« Contact me at juno.stump@gmail.com if you need someone with experience in mock reviews, copy editing/writing, PR work, etc »

Words: Juno Rylee Schultz (she/her)

Edits: Morgan Shaver (they/them), Nathan Miller (he/him), and Bex Stump (she/her)

“In SILENT HILL 2, fear could be defined in terms of what you don’t see, makes you feel afraid. If you know that there is something around that you can’t see, you’ll be scared—deep down. Psychological horror has to shake human hearts deeply. Shaking people’s heart deeply means uncovering people’s core emotion and motivation for life.”

— SILENT HILL 2 Producer Akihiro Imamura

“Movies didn’t inspire my work for creation of SILENT HILL 2’s music; that’s just my style. I think that the sounds in Resident Evil are pretty formal … [sounds] we are used to hearing […] [F]or SILENT HILL 2, I really tried to create something that would surprise you [and] challenge your imagination—as if the sounds were going under your skin. What I mean by that is to create a physical reaction for the game player—such as a feeling of apprehension and unease.”

— SILENT HILL 2 Sound director and composer Akira Yamaoka

“I wanted to create something that would really disturb the game players whilst attracting them; something with an aura of mystery. At the beginning of the game, we deliberately made the descent through the forest towards the cemetery longer. It’s so long you don’t feel like turning back [while also understanding] just how totally isolated the city is. We knew it was a bit risky, in terms of gameplay, but we really wanted to take our chances and do it.”

— SILENT HILL 2 Art Director Masashi Tsuboyama

“My basic idea in creating the monsters of SILENT HILL 2 was to give them a human aspect. In the beginning, the game player would believe they were human. Then I proceeded to undermine this human aspect, by giving weird movements to these creatures, and by using improbable angles for their bodies …”

— SILENT HILL 2 Monsters designer Masahiro Ito

Developers of SILENT HILL 2 discussing its creation, The Making of Silent Hill 2

Silent Hill was designed to feel like it could be any American town—with its dreariness and melancholic curse, summoned from sins of indifference and colonialism. But inside the town is also a clear exploration of trauma, tragedy, and what happens to pain and people with the passage of time.

SILENT HILL 2 is a narrative —and a digitally, constructed Shakespearean stage—built for the sole purpose of exploring the everlasting ripples of a human soul’s actions, and how seeking out violence and pain for catharsis cannot offer existential redemption. Everything breaks, everything dies, and every statue memorializing a lost life inevitably fades—whether we admit it or not. But the undoing of threads doesn’t need to be the end.

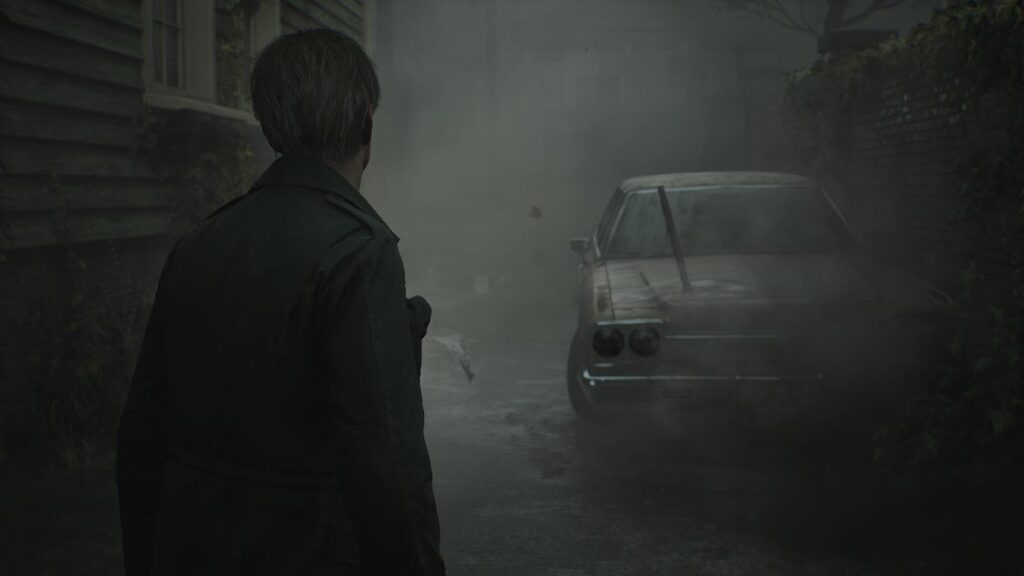

James Sunderland parking his car crooked, and staring into his eyes, as he—and the player—look into the bathroom mirror is how the player and James first meet. The gameplay itself starts whenever players decide to break the honest self-examination to begin looking for Mary inside the town of Silent Hill, even though she’s already dead.

“We decided to just focus the story on the character of James … We thought that if we were going to focus on story, we needed to do something that would stand out a little, which is why we made the decision for the protagonist to… well, it’s not the official ending, but we showed him committing suicide, something rarely seen in video games at the time.”

Masahiro Ito speaking about the development of SILENT HILL 2, IGN Japan 2023

“There was a feeling among the development team that we were going to challenge ourselves to make something never before seen in video games. The team happened to contain a lot of members who approached things in ways you wouldn’t expect from game developers, including the kind of movies and novels they’d experienced, [Dostoyevsky’s] ‘Crime and Punishment’ included. We all loved works that you could consider literary, as you put it, or minor. When all of that energy was added and multiplied together, though, it turned into something major, resulting in the work it became.”

Akira Yamaoka speaking about the development of SILENT HILL 2, IGN Japan 2023

Not all who wander are lost … except everyone who wanders into Silent Hill disoriented, blissfully chasing unawareness. Every visitor seems able to subconsciously ascertain they’re not meant to be there, but that knowledge isn’t enough to stop them or encourage resistance against the town’s sinister pull.

A key part of SILENT HILL 2 is that James Sunderland wasn’t captured and forcibly brought to Silent Hill. James drove to the town with his own free will. He wants to be here, regardless of how uncomfortable it feels.

The game would remain most comfortable if James—and the player—would commit to never entering the town. But ultimately, it cannot be helped. James and the town insist upon themselves, and with each step further into Silent Hill, the cuts in reality deepen.

“It can be insulting to a game to say ‘the story is all that matters,’ but SILENT HILL 2 drives its story through the gameplay. The more we play, the more hesitant we are to continue playing. Without the ability to get bigger, or stronger, each step is more worrisome than the last. With each discovery that James isn’t what he appears, we’re less compelled to want to help him. The game makes us question ourselves and our role in a cycle of violence. “

Silent Hill is a town that used to go by a different name, long before it was overrun by monsters, and before cultists and ancient gods began taking notice of it—but that name has long been forgotten. Terror and tragedy are consistently found within the town’s history, from newspapers to notes, all left behind by everyone that used to live in the town—before they all up and left.

Everything in Silent Hill reeks of hell—including places that should feel “normal,” like the hospital.

Everywhere in town feels cursed and tainted beyond reach of anything bearing even the slightest resemblance of salvation. It’s all decorated—subtly occasionally—with references to prison imagery. Isolation is a central pillar of the town and game’s atmosphere, like Twin Peaks and other media framed around the incongruousness of Americana—and the normalized juxtapositions consistently presented by modern day capitalism. The town of Silent Hill wishes for comfort, but ultimately offers only suffering that’s both magnetic and repulsive.

There’s not a moment after entering Silent Hill that ever feels like yesterday was earned, or that will tomorrow will ever come.

The only satisfaction that can be derived from Silent Hill is from trying to pull it apart, break it open, and see why it can’t stop screaming—the same reason people pay it a visit in the first place. They can’t stop screaming, in a world that doesn’t allow a mouth for it.

Silent Hill is a puzzle that demands to be broken, solved, and silenced. Except … Silent Hill isn’t real, not even to those who wander there. But it doesn’t matter, it’s a place people are drawn to nonetheless.

“Welcome to Silent Hill!

Silent Hill, a quiet little lakeside

resort town. We’re happy to have

you. Take some time out of your

busy schedules and enjoy a nice

restful vacation here.

Row after row of quaint old houses,

a gorgeous mountain landscape,

and a lake which shows different

sides of its beauty with the

passing of the day, from sunrise

to late afternoons to sunset.

Silent Hill will move you and fill

you with a feeling of deep peace.

I hope your time here will be

pleasant and your memories will

last forever.”

— a SILENT HILL sightseeing brochure

The town insists upon itself and the visions of those drawn to it, all feeding on each other in a parasitic symbiosis masquerading as an unresolved mystery that might contain healing.

Silent Hill possessing a form of conscious and evil thought is confirmed by its monsters and the town’s surroundings—all of which are different to the individuals who wander there. The only central theme that seems to be shared between visitors of Silent Hill is contending with the fears, ignored truths, and each individual’s chosen perceived reality versus the world they’re seeking redemption and isolation from.

James Sunderland has been summoned to the town of Silent Hill by a subconscious, paradoxical manifestation of himself. He simultaneously wants to live, and die. Hungers for salvation, while also craving damnation. Wants to go back and stop, but absolutely can’t turn around. He’s condemned to moving forward.

James is every person who can’t handle their tragedies, in a world that often rewards violent power structures while brushing pain—and sins—beneath the passage of time.

When James meets Eddie, another man visiting Silent Hill, and mentions the monsters, Eddie has no idea what he’s talking about. All Eddie sees are James and the other “seemingly normal” people exploring the town. Eddie’s only fears inside the town are the judgment of James and others, which is projected onto James—and the player—during encounters between the two characters.

Angela, a teenage girl wandering the town, only speaks of fire and everything burning and hurting her. “You see it too? For me, it’s always like this.” Through conversations with James, it’s learned Angela was abused—likely sexually and physically—by her father, and possibly her brother. She’s already been hurt, so for her everything is burning—all around her—by default. She has no need to project monsters onto the foggy streets of Silent Hill.

Laura, a young orphan girl who James meets, acts antagonistic towards him during multiple events in the town, but through conversations and memos, players learn Mary was going to adopt Laura, until she died.

And then there’s James himself, wandering a hellish town with demons that specifically exist to haunt him—monsters that look like feminine-shaped bodies, thrashing and spewing vomit, without heads, hands, or feet.

There’s Pyramid Head, the sexually and violently aggressive beast, that ultimately has no interest in James, and instead largely serves to frighten him as it lashes out in grotesque and horrific ways at the game’s other monsters; Maria, who isn’t necessarily a baddie, but created by James to love and hate—to take care of and wish he could love like he wanted with Mary before he murdered her; and finally, the sexually-suggestive nurses, who do far more than claw at the eyes of this doomed antagonist we’ve been playing as.

The boring, mundane, but ultimately horrifying villain—and main character—of SILENT HILL 2. James Sunderland.

SILENT HILL 2 has multiple endings and ways to interpret how it ends, but the version that feels most canon and appropriate for the game’s tone, and atmosphere, and what everything has been thematically building to, is the ending where it’s implied James Sunderland committed suicide at the start of the game.

This ending is achieved by doing specific actions in the game—accessing items, focusing your attention on certain characters, how “James”(the player) treats himself—all encouraging James to focus on his guilt and desire to die.

When this ending is unlocked, a cutscene plays that implies James drove his car into the lake at the rest stop, looked in the mirror, and then began his haunting descent to the town of Silent Hill—his own personal hell—to atone for his sins and find a catharsis in suffering that would allow him to forgive himself.

This would make the events of SILENT HILL 2—the gameplay we experience, and all the events players bear witness to—James processing his actions and making an attempt to reach forgiveness through violence, suffering, and recognizing the pain he has caused.

This means other characters in the game—the people James meets in Silent Hill—are imagined and not real. Possibly extensions of his psyche and tormented memories. Or they could be real people, like James, and seeking some form of peace before entering into the next part of death, life, and whatever is next.

Regardless of the chosen interpretation of SILENT HILL 2’s story, James killed his wife because he hated that she wasn’t who she used to be before she fell ill. He resented her for him having to take care of her and his resentfulness is seen through every crowbar swing, against every twisting, wiggling, puking corpse.

It’s important to recognize and see the violent power fantasy that’s wrapped around the story of James Sunderland, and how violence and monsters aren’t a default part of the Silent Hill tourist experience.

“Failure is a frequent theme across the Silent Hill series, particularly regarding one of the most familiar play-motivating devices within video games: […] the male-hero-rescuing-helpless female trope endures, structuring all three of the male-centered Silent Hill games.

Masculinity in Video Games: The Gendered Gameplay of Silent Hill by Ewan Kirkland, Camera Obscura

The original Silent Hill sees Harry searching the town for his adopted daughter, a quest that reinforces patriarchal power relations defining men as responsible for the protection of both women and children. In Silent Hill 2, James returns to the town to rescue his wife from the underworld in which she is trapped. Each game, in its way, enforces the mythology of male as protector of the female, and, arguably, each player, in performing the role of Harry [and] James is structured into adopting a similar ideological position.

Silent Hill can frequently be understood as presenting a critical discourse on masculinity, rather than an enforcement of traditionally male narratives.

The landscape of Silent Hill reflects the guilt, anxiety, and misogynistic fears of these imperfect men. Certainly, criticisms that contemporary video games indulge players in a particularly unreconstructed mode of masculinity, which rewards violent action over imagination, emotion, or empathy and which actively excludes, marginalizes, or objectifies women, do have clear foundation in recent blockbuster titles. But a distinction must be acknowledged between the video-game industry, with its current emphasis on macho combat, and the medium itself, the potential of which has yet to be fully realized or appreciated even by those most closely involved in its production. The Silent Hill series is notable in this respect: a commercial franchise that works within generic and industrial constraints, yet manages to challenge traditional models of masculinity and their implication in conventions of video-game characterization, representation, and play.”

James Sunderland is bashing his head against what he is, what he hates, and what he wishes he wasn’t inside the imagined suffering, punishment and walls of SILENT HILL 2—with the inward hope and plea that with enough suffering he just might be set free.

Everything in SILENT HILL 2 conjures up feelings of guilt, pain, abandonment, and death—because it’s all James thinks he deserves—until he’s forgiven and forgotten, like all the other tragedies of Silent Hill. And every broken person to ever walk this world.

Leave a Reply